Physics lab courses are vital to science education, providing hands-on experience and technical skills that lectures can’t offer. Yet, it’s challenging for those in Physics Education Research (PER) to compare course to course, especially since these courses vary wildly worldwide.

To better understand these differences, JILA Fellow and University of Colorado Boulder physics professor Heather Lewandowski and a group of international collaborators are working towards creating a global taxonomy, a classification system that could create a more equitable way to compare these courses. Their findings were recently published in Physical Review Physics Education Research.

With a global taxonomy, instructors can have a more precise roadmap for navigating and improving their courses, leading to a brighter future for physics education worldwide.

“The ultimate taxonomy will help education researchers both understand physics lab education broadly and also be able to compare and contrast studies done around the world,” says Lewandowski.

An International Need for Global Mapping

According to Gayle Geschwind, the paper’s first author and a recently graduated JILA Ph.D. researcher, the project began as an international conversation between physicists who realized that comparing lab course assessments was not always straightforward.

“It can be hard for instructors to get useful information,” said Geschwind. “For example, a sophomore-level course can’t easily be compared to an introductory one, but right now, that’s often the only data available for comparison. Lab courses vary in how they're taught, the methods they use, and the equipment the students can interact with. And these lab courses are expensive; some use nice equipment, others aren’t able to.”

This mismatch prompted the researchers to develop a method that will eventually result in a database of the many different laboratory courses for physics across the globe.

Starting with Surveys

The team’s first task was to build a robust survey to capture how lab courses are structured worldwide. The researchers started with a brainstorming session that was then refined into a more extensive survey to address course content, the kinds of equipment available, and how students were assessed.

Once the survey was ready, the team interviewed instructors from 23 countries to ensure the questions were clear and applicable to different educational systems. From these early interviews, Geschwind, Lewandowski, and their collaborators improved their survey. While the earlier editions had options for instructors to put in the major and minor goals of the course, based on the feedback from the interviews, the team decided to add an option for a future goal, where an instructor could add other techniques students could learn in the future.

Along with the improvements to their survey, Lewandowski and Geschwind found a challenge early on in the phrasing of some of the survey questions.

Geschwind shared a telling anecdote: “Heather and I spent three or four hours on one question’s wording about how many students are in each lab section... It turns out ‘lab section’ doesn’t mean the same thing outside the U.S., and eventually, we had to phrase the question very creatively to get our point across.”

Beyond the language issues, the team discovered surprising differences in lab structures. In some countries, labs might meet daily for two weeks rather than weekly throughout the semester. Other differences were more extreme, like an interviewee based in Africa who shared that students sometimes had to “stick screwdrivers into electrical outlets” just to see if the power was on that day—a stark contrast to the well-equipped labs in wealthier nations.

Finding the General Themes

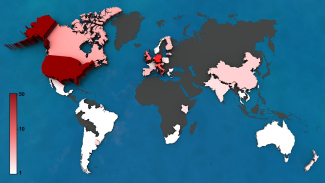

After finalizing the survey through an iterative process of interviews and revisions, the team sent it to their network of lab instructors, asking them to complete it and share it with others. While the researchers initially gathered responses primarily from Western Europe and the U.S., they soon expanded their efforts by compiling a list of every country and cold-mailing institutions worldwide. To their surprise, they received many responses, including from regions historically underrepresented in STEM, helping enrich the global database of physics lab courses.

From the survey responses, the researchers found some prominent initial themes. Across the board, lab courses emphasized technical skills and group work. Geschwind was fascinated by the fact that “an introductory mechanics lab course doesn’t differ much from place to place” despite the variety in equipment and resources.

Another interesting result was about the number of learning goals instructors have for their students in the courses. On average, instructors identified nearly 12 distinct goals per course, highlighting the complex nature of laboratory environments as part of courses designed to foster a broad range of knowledge and skill development.

Perhaps one of the survey's most unexpected outcomes was its immediate impact on the instructors who took it. Many began rethinking their own courses during the process.

“They’d see something in the survey and go, ‘Oh, that’s a cool idea! We don’t do that, but I’d love to implement it,’ ” Geschwind noted.

In fact, the survey even included links to resources and best practices that participants could explore, making it a research tool and a learning opportunity for the instructors.

Creating a More Thorough Map

Looking ahead, the research team has big plans for their data. The ultimate goal is to create a global database of lab courses, and standardized categorization of these courses, that can help instructors compare and improve their teaching methods. Geschwind explained that this database could be beneficial for instructors who want to redesign their courses, as it would allow them to see what others are doing in similar classes worldwide.

“We eventually want to get this database of information...so if an instructor wants to restructure their electronics course, they can see what others are doing,” she added.

The project is currently unfunded, with most of the team volunteering their time, but that hasn’t stopped them from envisioning future developments. Geschwind suggested that in the future, the team could use clustering algorithms to group similar courses and identify trends, such as whether certain types of lab courses, e.g., second-year electronics labs, unexpectedly share similarities with others, such as senior-level quantum labs.

As the project progresses, the team hopes to gather more data, particularly from underrepresented regions, to make the taxonomy even more comprehensive.

“Eventually, this could lead to better assessments and more informed teaching practices, making physics lab education stronger globally,” Geschwind said.

This research was supported by the National Science Foundation.

Written by Kenna Hughes-Castleberry, JILA Science Communicator