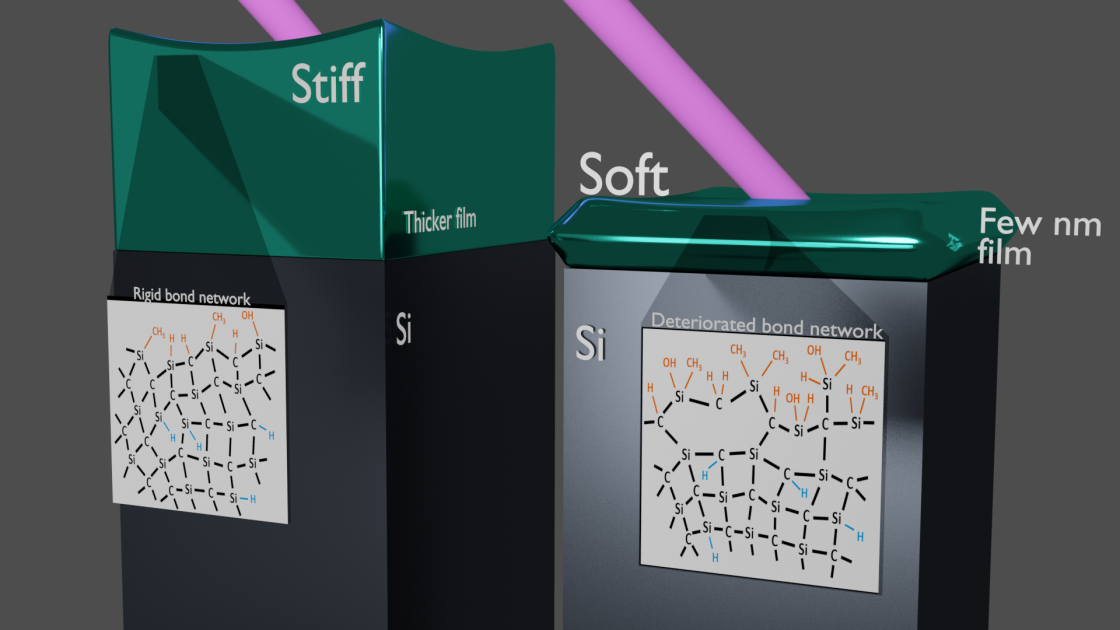

CU Boulder researchers have used ultra-fast extreme ultraviolet lasers to measure the properties of materials more than 1,000 times thinner than the width of a human hair.

The team, led by scientists at JILA, reported its new feat of wafer-thinness in the journal Physical Review Materials on July 13. The group's target, a film just 5 nanometers thick, is the thinnest material that researchers have ever been able to fully probe, said study coauthor Joshua Knobloch.

"This is a record-setting study to see how small we could go and how accurate we could be," said Knobloch, a graduate student in the KM Group at JILA.

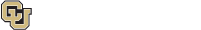

He added that when things get small, the normal rules of engineering don't always apply. The group discovered, for example, that some materials seem to get a lot softer the thinner they become.

The researchers hope that their findings may one day help scientists to better navigate the often-unpredictable nano world, designing tinier and more efficient computer circuits, semiconductors and other technologies.

"If you're doing nanoengineering, you can't just treat your material like it's a normal big material," said Travis Frazer, lead author of the new paper and a former graduate student at JILA. "Because of the simple fact that it's small, it behaves like a different material."

"This surprising discovery—that very thin materials can be 10 times more flimsy than expected—is yet another example of how new tools can helps us to understand the nanoworld better," said JILA Fellow Margaret Murnane.