Your Full Name: Joshua (Shuka) Schwarz

Briefly describe how you knew Jim: I was one of Jim's last grad students, ~1994-1998. It was just the two of us until Artyom joined us. I spent time working in the machine shop building compact springs of a design that Jim came up with (I think we got a 60s period in a ~4 cm tall spring, but not very stable), then worked on a G measurement that I think Tim Niebauer conceived. Jim also supported my education in wine, music, dance, and satirical comedy/science standup.

Your story, comment or memory: The best thing about Jim was his contagious enthusiasm. Imagine a problem you'd like to solve ( or a wine you'd like to taste, a song you'd like to sing, some recorder music you'd like to play ... ). Now get excited about it! Somehow Jim could amplify your ideas and simply your enthusiasm to tackle/try/explore. I'm hoping that just rememebring him will continue to provide at least a shadow of the effect.

I'll miss many things about him. He had a tremendous impact on my outlook about science, and was really the first person to demonstrate to me that the ability to make progress in science did not require conformity with any other person's approach to problems. That's a take-away that I think every young scientist should feel in their hearts.

Jim was tremendously bold when it came to humor and voicing unpopular opinions. Boldness is something very hard to teach (I didn't), but can be passed on as inspiration. In that vein I attach one of Jim's very favorite cartoons, which he would modify according to whim and need with different headings. I am scared that it will offend, but is not meant to, and is triply-inspired by Jim. Back then he was my mentor and I was his only grad-student. From now on, for me, he will continue to be a guiding star in my night sky, and continue to inspire me to take more chances than I'm comfortable with when I hope that they will help.

Jim and Jocelyn "began" when I was working with Jim, and my memories of him are intertwined with those of her, and his enthusiasm and admiration for her. I always felt that Jocelyn liked me, and this was at least half the reason that Jim liked me. Thank you, Jocelyn, for helping to to experience more of the best side of Jim!

Your Full Name: Harold Parks

Briefly describe how you knew Jim: I was Jim's post-doc from 1998 to 2000 working with him on a Newtonian constant of gravitation experiment.

Your story, comment or memory: Jim was one of those uncommon bright lights that mark out the life of those fortunate enough to meet him. Though he could definitely be outspoken, his sometimes sharp wit directed towards those who could defend themselves was always exceeded by his kindness to those less powerful.

Click images for larger view (when available)

Your Full Name: Steve Moody

Briefly describe how you knew Jim: As a teacher, mentor, and thesis advisor as a Wesleyan undergraduate.

Your story, comment or memory: I want to highlight one aspect of Jim’s approach to life, which was his way of opening horizons for students. I’m thinking specifically about the Lunar Ranging experiment, for which Jim’s group of 6 students (5 undergraduates, mostly Juniors, + 1 graduate) achieved the first successful lunar returns.

This manifestly unqualified group designed and built our piece of the project in about 1 academic year. By any objective measure this should have entirely beyond our capabilities. Jim’s magic was to define a working framework that only contained one path. We would learn what we needed to learn, do what we needed to do, correct what we needed to correct, and arrive at the goal. Nothing else could or would be imagined.

And we did!

It is only in the last few years that I have come to realize how much that experience defined my life going forward.

Click images for larger view (when available)

Your Full Name: James (Jim) A. Hammond

Briefly describe how you knew Jim: I met Jim when I started my PhD program in the physics department of U of Colorado in the fall of 1963. I was a TA for the first class he taught there and then in 1964 started working on the "world's first transportable instrument to measure the absolute acceleration of gravity". Jim was, of course, my thesis advisor.

Your story, comment or memory: Jim and I arrived at the University of Colorado at pretty much the same time, in the fall of 1963, I to start graduate school in the department of Physics and Jim to join the newly formed JILA as a postdoctoral researcher after completing his PhD at Princeton University. With a great deal of fortuity guiding my naïve way through the course of my academic career, I first had a position as a teaching assistant working with Jim in a course based on the remarkable text book, Physics for the Inquiring Mind, by Eric Rogers. The title of this book, alone, provides a testimony to what I learned by working with Jim through approximately seven years we were together during my PhD studies and thesis research. An ever inquiring mind is a good way to summarize Jim Faller’s intellect and motivation in life.

Starting on a project to build a new instrument to measure the acceleration of gravity seemed like a good idea for a thesis project and so I accepted Jim’s invitation to become part of the project that would continue his doctoral work and go on to involve many other students and instruments over the years, up until his passing. We continued to cooperate on systems related to the measurement of the acceleration of gravity up until I moved to a position in the aerospace industry in 1982. Unfortunately, we had little contact over the years since then. The last time we traded emails was in 2017 when Jim asked if he could get a copy of a movie I had made of our instrument operating and being packed for shipping before one of our “expeditions” in 1968 or 1969. He wanted to use it in a talk he was giving in Beijing later that year. As the only person seen in this movie is Tuck Stebbins and Tuck is featured during this memorial event, I think it would be ok to give the link to the youtube of that movie here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eJ_5nRDLSMU

I was not able to find any good photos of Jim and me together during my PhD work either at JILA or at Wesleyan University where I finished my thesis work before receiving my PhD from UC. So this video will have to suffice as an illustration for this remembrance.

In the days since I learned of Jim’s passing, I have thought frequently about what I could write in a remembrance without being too wordy for the occasion and still provide some kind of view of what my long connection with him has meant to me. We’re talking about essentially 60 years now. There are not a vast number of people included in the collection of remembrances who go back that far.

Some of the lessons that have stuck with me from my working with Jim have come to mind in thinking about writing this brief note. The inquiring mind is certainly one aspect that I hope I’ve continued to have through my 40 or so years of professional work and even continuing until now with lifelong learning programs. The stubbornness of sticking to solving a problem until is solved (or until the time or money runs out) is something I learned from Jim. I still have a list of unsolved mysteries that I hope to solve before I have to go. Jim could be a stern teacher and task master but he never failed to stand by his students and co-workers to work on the problem rather than just checking in infrequently to see how you were progressing.

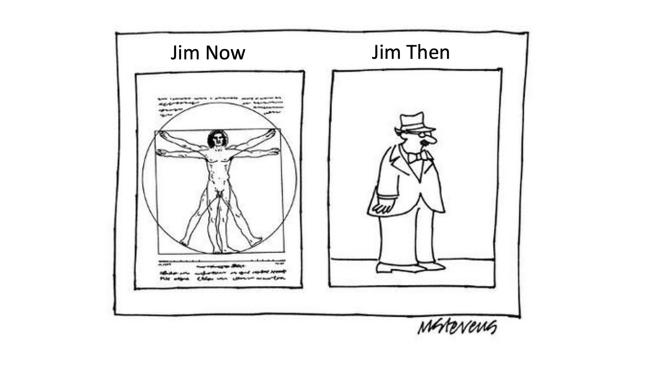

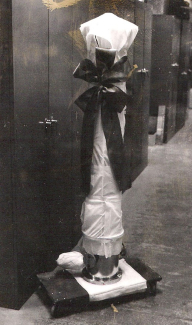

Just recently, because I saw a reference in the announcement of the memorial gathering to the “JILA Shops Fund”, I was reminded of the great regard he had for the technical support received from the JILA and Wesleyan shops. (And certainly, too, for other such support to the many projects he has been involved with.) He knew and passed on to me, I think, just how much any successful research or scientific project needs talented and dedicated shop workers and other technical staff. One photo I just found today is of the first mechanical assembly of our main vacuum chamber presented to me wrapped as though for a Christmas gift by the JILA shop.

My sincere condolences to all of Jim’s family and friends, I join all of you in feeling a great personal loss.

Jim Hammond

Your Full Name: Bill Hollander

Briefly describe how you knew Jim: I met Jim when I applied for a job in the JILA instrument shop in 1979. He was in charge of the shop committee at the time and seemed to think that a young Porsche mechanic and photographer had potential to become an instrument maker in the JILA tradition. I spent roughly half my 11 years in the JILA shop working with Jim on gravimeters, Eotvos experiments, fifth force experiments, laser stabilization, and more.

Your story, comment or memory: In an unconventional fashion, Jim was my advisor and Doktorvater. Unconventional in that I was not a student at all, but a newbie instrument maker whom Jim cultivated and commandeered to work on his gravimeters and other projects. I was eager to learn all I could about physical instruments and Jim obliged, along with the pros in the JILA shop: Bill Lees, John Andru, Hans Rohner, Dave Hendry.

At the time I was hired, work was being completed at JILA on Jim's third generation absolute gravimeter. He had built his first-generation gravimeter with a white light interferometer as a grad student at Princeton, the second generation at Wesleyan. The JILA generation 4 instrument was to be designed and built in a batch of five units, funded by, among others, NOAA, the Defense Mapping Agency, and the Geological Survey of Canada. I was thrown into the deep end of the pool, and he began teaching me to swim, combining physical instrument design principles, background from previous generation instruments, and manufacturing approaches to consider, along with humor and badinage, and applying that knowledge to the construction of the gravimeters. Alas, progress on the batch of meters was very slow and it was consuming much of the shop's capacity. By that point, possibly out of desperation, Jim had developed enough confidence in me that he also tasked me with project managing the construction of the instruments. Tim Neibauer was doing his degree work on the electronics, optics and control systems for absolute gravity measurement. The three of us worked closely for the years of the construction and commissioning phases of the project. This is where I learned from Jim how to argue, both from positive and negative examples! Jim was fond of creating physical representations of his ideas from cardboard and plywood. We often debated over the merits of more or less sophisticated models or prototypes. In 1985, as the first of the gravimeters were being completed, an intercomparison of g-meters at BIPM in Paris was fast approaching. There was a genuine concern that we wouldn't be done in time. To allow for final assembly and alignment to be completed on site at BIPM, Jim became convinced, or I convinced him, that I should be part of the contingent from JILA travelling to Paris. There was no precedent for an instrument maker to be paid to attend such a conference but Jim thought it would be good insurance and somehow wrangled the approval. As it turned out, Tim and I completed the instrument and made successful measurements in the basement hallway of the BIPM while Jim lay passed out on the floor, having contracted a terrible cold or flu while we travelled. Terry Quinn, the BIPM director, kept coming down to our hallway laboratory to check on our progress and Jim's health, often shaking his head in concern and/or amusement. The gravimeters were finally delivered and I moved on to work with Jim on other projects as well as with the other JILA experimentalists.

Jim always brought his sardonic sense of humor and great physical insights to those projects. He bridled at being constrained by administrative inertia. The cartoon of Gulliver being tied down by the Lilliputians was a frequent presence in Jim's lecture slide shows along with illustrations of the physics of basketball.

Eventually those who received the generation 4 gravimeters wanted to obtain more. The JILA fellows were determined, however, that such a large manufacturing project would not consume the shops’ capacity again so I began to initiate a technology transfer that involved both NIST and CU. Jim was closely involved in this process although it was unexplored territory for JILA in 1989. We finally negotiated all the contracts and I helped to found Axis Instruments Company to commercialize the gravimeters. Jim was supportive of this process and we worked together closely as Axis developed and built the next generation absolute gravimeter, named the FG-5 for Faller's generation five in his honor.

I went on to found High Precision Devices (HPD) after Axis Instruments was closed in 1993. The FG-5 gravimeter was transferred to Micro-g Solutions and Jim was a supportive presence there for many years after.

Jim continued to follow my instrument development ventures. In the late 1990s and beyond he made many pilgrimages across Boulder to HPD as we developed a prototype seismic isolation platform for LIGO with Tuck Stebbins and Giles Hammond, based on work Jim had done on synthesized long period springs for his gravimeter Superspring. This was followed by two more generations of seismic isolation platform, the last of which was installed in the Advanced LIGO interferometer that made the first detection of gravitational waves.

To say that Jim Faller was an important influence on my professional career would be a gross understatement. He gave me my start as an instrument maker and stayed connected throughout the years as I applied the principles and methodologies I learned in his labs.

Your Full Name: Edwin Williams

Briefly describe how you knew Jim: I was Jim's PhD student at Wesleyan from 1966 to 1970.

Your story, comment or memory: In 1964 I began the PhD program in physics at CU with the late Dr. Gordon Dunn. After 2 years, I failed my qualifiers and had to leave CU with an MS in physics. Although I didn't know Jim well then, he invited me to join him and Dr. Henry Hill in the newly established PhD program in physics at Wesleyan University in Middletown, CT. I was glad to accept this new opportunity. After my first year at Wesleyan, I was invited to join the physics program at Yale, but I was very pleased with my progress at Wesleyan and decided to stay where I was. With Jim's guidance, I was able to complete my thesis of setting an upper limit of the photon rest mass by an experimental test of Coulomb's law. I finished my PhD in 1970 and did a 1-year post doc at Williams College in Williamstown, MA, where I also competed with several hundred other physicists for an Assistant Professor teaching position. I was not the successful candidate, but I did land a position at the National Bureau of Standards (NBS, now the National Institute of Standards and Technology, NIST), where I enjoyed working in precision measurements from 1971-2008. I last saw Jim at the 2018 CPEM (Conference on Precision Electrical Measurements) in Paris, where we all celebrated the imminent vote to accept the new atomic definition of the Kilogram, of which I had been a part. I am grateful for Jim's invitation and his guidance through my 4 years at Wesleyan that put me on the path to a successful career in experimental physics.

Click images for larger view (when available)

Your Full Name: David Newell

Briefly describe how you knew Jim: I first met Jim when I joined the JILA gravity group as a graduate student in 1988. We’ve been bantering back of forth since.

Your story, comment or memory: I spent my first summer as a graduate student at JILA (1988) breathing life back into a ‘super spring’ under Jim’s supervision. He quickly made me realize that it is better to have a sense of humor when undertaking a serious project. He provided comic relief at critical moments and from his years of experience of developing exquisite precision instrumentation gave me design advice, useful working models, and a kick in the back side whenever needed through some backhanded comment the way that only Jim could serve up. The result of his guidance was a multi-degree of freedom active vibration isolation system architecture that was incorporated into the LIGO detectors. His intuitive insight, elegant approach, and exquisitely simple solutions to measure the unmeasurable formed the foundation of my future career.

Click images for larger view (when available)

Your Full Name: Scott Diddams

Briefly describe how you knew Jim: I was a postdoc at JILA in the late 1990s when Jim was the NIST Quantum Physics Division Chief

Your story, comment or memory: Jim was an amazing scientist with exceptional physical intuition and simple models to explain complex problems. Although Jan Hall was my supervisor, Jim was my official “boss”. Aa an NRC postdoc, that meant I had an annual performance review with Jim. We usually talked a little about my work, but then things turned to an educational session for me as he shared his insights into the optical and mechanical systems surrounding his Big G measurements. I was lucky to get to spend time with Jim on such occasions, as well as at the basement lunch table. I’ll never forget those invigorating discussions and Jim’s love of a clever solution to a hard problem.

Click images for larger view (when available)

Your Full Name: Timothy M. Brown

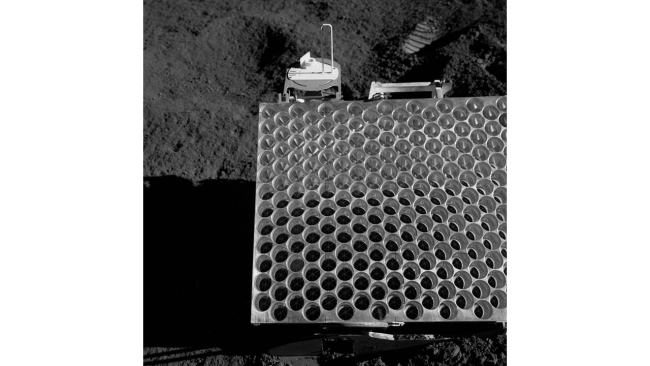

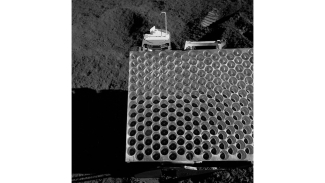

Briefly describe how you knew Jim: As an undergraduate at Wesleyan University and later as a graduate student at CU/Boulder, I worked with Jim for about four years, mostly on the computer control system for his Multi-Lens Telescope, which was to be used for lunar ranging.

Your story, comment or memory: I first got to know Jim Faller in the fall of 1969, when I walked into his basement office in the Wesleyan physics building and asked him for something to work on. What I chiefly remember from that meeting was his virtuoso recitation of Things That it Is Useful to Know if you want to do experimental physics. This list included: The thickness of a 3x5 card. The width of a quarter. The weight of a nickel. The utility of old copper pennies as support points for instruments (because the metal was soft). How half-deflated playground balls could be used for vibration isolation. The thermal expansion coefficient of pretty much any material you could name. And so on. In short, the guy knew things. And he made it clear to me that if I wanted to be any good at this business, I had better learn some of those things too.

Our second meeting carried a deeper lesson. He asked me to do a simple beam-deflection calculation. Given a steel I-beam of certain dimensions, if one supported it in the middle and loaded the ends with a 1-ton telescope, how much would the ends flex? He pointed me to the appropriate formulas in the Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, and turned me loose. In due course I returned with my answer, which was about four-tenths of an inch. His face scrunched up and he flashed that grin of his and he said, "That can't be right. It should't move more than a millimeter." So we got out the formula and our slide rules (we still used slide rules in those days), and pretty soon we discovered that I had misplaced the decimal point; his answer was right, and mine was wrong. Now for me, the point was not only that he got the right answer, but, astoundingly, that he didn't have to calculate anything to get it. He had enough insight and experience with how things work in the physical world that he could just visualize how the system was put together, and come up with the number--in this case, to better than ten percent. For a wide range of interesting physical systems, he had quantitatively reliable intuition. Like, WOW. I wanted to get me some of that.

Over the next few years I managed to acquire from him some of those skills, and others besides. I learned a lot of stuff. Enough, in fact, to get me through a long and decent career in astronomy (though of course, other people mattered too.) So all this reinforces my feeling that if you want to understand how a physicist works, you shouldn't ask where they went to school, or what courses they took. You should ask the same as for a jazz musician: who were their influences? And I am grateful and proud to be able to claim Jim Faller as my first and one of my own most important influences.

Click images for larger view (when available)

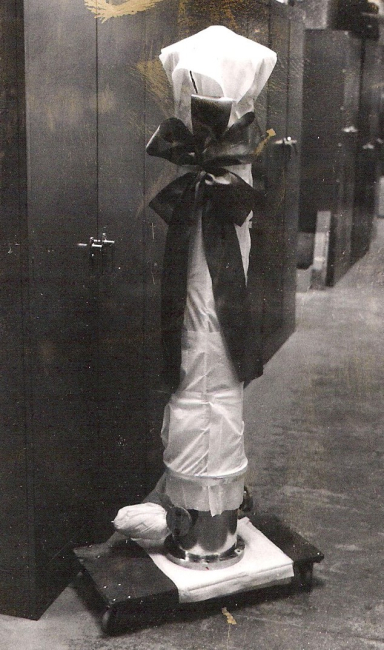

Your Full Name: WU Shuqing

Briefly describe how you knew Jim: I knew Jim by email at first,because our group are developeing the absolute gravimeter for metrology. Then Jim visit our institute in 2006 and 2010.His broad mind and profound knowledge infected me deeply.

Your story, comment or memory: Jim Faller have contributed a lot of to our gravimetry group in NIM China (National Institute of Metrology,China) and gived me great help and support.please accept my sincerest condolences.I will remember and memory Jim Faller forever.

Your Full Name: Artyom Vitouchkine

Briefly describe how you knew Jim: I worked with Jim from 1996 until 2004. He invited me to JILA work on absolute gravimeter project

Your story, comment or memory: I met Jim in France around 1994-95 and later he invited me to work in JILA on absolute gravimeter project. At this point I just got my masters degree in physics and had some experience with field gravity measurements. However I had no idea how to envision, design and build any type of scientific instrument.

Jim softly nudged me into the right direction and under his guidance we built absolute gravimeter. Eventually we took this instrument to BIPM, France for gravity intercomparisons in 2005. We got very good results.

And to this day I am still designing and building scientific instruments, including atom optics gravimeters. All thanks to Jim, I can't pinpoint exactly how he did it, but he did turned me into very good scientist/engineer.

Here some pictures I have from 2005 taken at BIPM, France.

Your Full Name: Spencer Weart

Briefly describe how you knew Jim: I was Jim’s PhD student at JILA and Wesleyan 1964-1967

Your story, comment or memory: I was in Jim’s first group of doctoral students, but he already understood how to handle the job of what the Germans call a “Doktorvater.” He took me on as a student when other professors doubted my talents. He guided me so well that although I do indeed have far less talent as a physicist than Jim, on leaving Colorado I could go straight into a dream-job postdoc at Mount Wilson/Palomar and Caltech. Jim was particularly good at conveying a deep understanding of instrument-building. That might seem natural in somebody who was fresh from his own studies at Princeton under Bob Dicke, but I believe Jim surpassed even the formidable Dicke in the wide-ranging ingenuity that is the hallmark of the true classical physicist. Jim was good with people too, of course. Among many things that stick in my mind, I’ll mention just one. After some frustrating experience that I wasn’t privy to, he remarked, “Getting things done with people is like building a skyscraper out of toothpicks and rubber bands.” If anybody could accomplish such a task, with people or with actual toothpicks, it was Jim. He made the world a better place.

Click images for larger view (when available)

Your Full Name: William Stuart Trimmer

Briefly describe how you knew Jim: Jim was my graduate student advisor at Wesleyan University.

Your story, comment or memory: Jim taught me how to work and think as an experimentalist. His impact on my life has been enormous. I called him about 10 years ago and thanked him. Recently I thought about calling him again.

Jim used to work until about 2 in the morning. I knew he was exhausted, but he would see me in my lab, and would always stop and give me 15 minutes. I thank him so much.

Click images for larger view (when available)

Your Full Name: Robin "Tuck" Stebbins

Briefly describe how you knew Jim: I started work with Jim as an undergraduate research assistant at Wesleyan in September 1966.

Your story, comment or memory: The First Semester for Free

Jim Faller introduced me to experimental science, and it wasn’t gentle. He and I have had a 57 year-long jesting match, which we both enjoyed immensely, but I can’t walk away from without a last blow.

You didn’t have to know Jim Faller well or long to know that he was scrupulous with his nickels. When I first walked into Scott Lab in early September 1966, I was looking for work in the Physics Department. For someone who had never been in a physics lab, it was beyond frightening. The 1873 building was intimidating. I was sent to Jim’s office in the basement, which could have been a dungeon if only they could find some prisoners. There was litter and debris everywhere, coax cables crossed the hallway floors from one room to another. There was an ominous cloud fog streaming out of the men’s room and down the hall from the liquid nitrogen machine in there. In the caves that looked like they housed squatters, there were dried out tea-bags in beakers on ring stands with Bunsen burners.

I encountered Jim at his desk with both feet on the desk, or at least on the papers that buried the desk. I introduced myself and enquired as to whether he might have an employment opportunity. I hastened to point out that I qualifies for work-study, thinking that would sweeten any deal.

In the day, an approved work-study student would receive $1.50/hr for approved work, of which the federal government would pay $1.37/hr, and the generous faculty would throw in the remaining $0.13/hr. But that was too much for Jim.

He intimated that there might be work for a qualified individual, but he would need to know my skills before making the big commitment. He then proceeded to interrogate me about skills, like machine-shop operation (no I couldn’t operate a lathe, no I didn’t know what a vertical mill was), optics (no, I had no experience with lasers, I didn’t know how to assemble optical systems), electronics (no experience making circuit boards, scant exposure to basic instrumentation), and so on. He surely guessed beforehand that I knew none of these things. I was left wondering what I did know.

In a fit of big-heartedness, he offered to let me work for free for a semester to see if I could truly earn his $0.13/hr.

Which I agreed to.

In the end, I’m the winner. It changed the trajectory of my life. And I paid a substantial chunk of my undergraduate education testing materials for the lunar retroreflectors, analyzing ‘g’ data for Jim Hammond, soldering a 3-layered icosahedron for Ed William’s test of Coulomb’s law, and working on many other inventive experiments. Jim’s guidance led me to JILA as a graduate student, and our 6 decades-long friendship.

Click images for larger view (when available)

Your Full Name: Robin "Tuck" Stebbins

Briefly describe how you knew Jim: I started work with Jim as an undergraduate research assistant at Wesleyan in September 1966.

Your story, comment or memory: Making a Retroreflector Overnight

In the early days of the lunar laser ranging project, Jim was vigorously promoting a design for the retroreflectors based on an array of modest sized corner cubes. There were competing proposals for one big giant corner cube from an Air Force lab.

As you would expect, Jim was exasperated that the other contenders did not see the many advantages of his design. On the day before Jim traveled to a design review, he decided that his design would seem so much more convincing if he had a model. In a burst of enthusiasm, he got one instrument maker to bang out a frame that he could mount on a small table-top camera tripod. But where would he get a dozen retroreflectors to populate the frame. And it would best if those retroreflectors retro-reflected.

He recruited a second instrument maker to cut off sections of a 2” diameter lucite rod, machine corners on one ends, a flat face on the other end and a mounting rim around their circumference. By mid-afternoon, all he needed were optical surfaces on 4 faces of all the corner cubes.

He accosted Al Healy and me to hand polish them with rouge before the sun rose. Undergraduates can be a soft touch for impossible schemes, regardless of the consequences for alertness in the next day’s classes. We agreed to give it a go. Al and I polished all night, and by morning, we were groggy and stained red, rouge slurry was everywhere, and you could see a retro-reflection in the cubes.

Jim went off to the design review with the model in his luggage, and his design was selected. Another triumph for Jim’s creativity and drive.

Bonus points: About 40 yrs later, I met Steve Ritz, a rising star of astrophysics now at UCSB, who exclaimed that he had seen the model retroreflector in a display case and it had inspired his career as well.

Click images for larger view (when available)

Your Full Name: Robin "Tuck" Stebbins

Briefly describe how you knew Jim: I started work with Jim as an undergraduate research assistant at Wesleyan in September 1966.

Your story, comment or memory: Apollo 11 Landing

Most physicists will remember Jim Faller for his contributions to lunar laser ranging. However, few will have the memory that those of us who were in the pit under the Lick 120” had. In July 1969, Jim brought 5 Wesleyan undergraduates (Steve Moody, Barry Turnrose, Dick Plumb, Tom Giuffrida, and myself) and one graduate student (Irv Winer) to Lick Observatory, east of San Jose on Mt. Hamilton, to shoot a pulsed ruby laser at the Apollo astronauts in the first-ever landing of humans on the Moon.

A pit, lined with tile reminiscent of a swimming pool, had been excavated under the 120” so that we could feed laser beams up through the prime focus and out towards the Apollo 11 landing site on the Moon as a large diameter beam. There was also a group from Goddard operating another laser and timing electronics.

The challenge at hand: the anticipated landing zone was an oval bigger than the laser beam size at the surface, and we had to know where in the zone the Lander put down. Houston had no direct way of knowing where in the zone the craft landed. And, as history has recorded, Armstrong flew the lander long until it was almost out fuel looking for a suitable landing site.

Jim had worked out a system for sighting on the zone with a reticle that had crosshairs that would align on three identifying craters and which could be offset. After the craft landed, Houston would estimate where the landing had happened from rudimentary flight data to suggest where in the oval we should start searching. Note that we expected a couple of photons peer return, under optimal conditions. Searching many beam diameters was a fraught process.

In the last days before the search began, Jim asked me to step away from the preparations and recalculate the return rate from first principles. My undergraduate self was shocked at getting the same answer.

The landing coordinates were conveyed over a telephone that had been installed in a small cavity below the observing deck and next to the swimming pool. It was also next the screaming oil pump for the telescope’s main hydraulic bearings. This would be my undoing, as I recorded the coordinates from Houston despite the oil pump in my other ear.

Having aligned our optics with the telescope and the laser beforehand, we began the process of ranging shots, searching across the landing zone, re-checking alignments, and looking for some photon to squeeze through a narrowband filter and a range-gate. Nothing. Nothing for days. Eventually, Jim thought to check the coordinates, and I had indeed mis-heard one, to my eternal mortification. The first ranging successes happened after that, a true triumph of Jim’s dogged perseverance.

The Goddard laser blew a cooling fitting, filling the container with water until it overflowed into the pit as we all watched in horror. It was a vivid reminder of what was possible.

But in the end, Jim led 5 undergraduates and one graduate student, with a past as a laser technician and a Los Angeles cab driver, to successfully make precision ranges to the Moon, a revolutionary measurement that looks to outlive us all.

Click images for larger view (when available)

Your Full Name: David Nesbitt

Briefly describe how you knew Jim: I knew Jim since my earliest days as a Fellow at JILA, which is now some 40 years ago.

Your story, comment or memory: Jim had a deep love of classical music, particularly recorder and choral music, which is probably where we first connected through the Bach Festival. He also was my go to guy for the CU Wizard show on The Physics of Music, where he would make (and play!) a French horn out of a metal funnel and a long coiled garden hose! Jim had deep insights into nature of precision measurement from which I learned a great deal. He had the lovely ability to distill a complex idea into very simple components, always claiming that he could only understand the simplest of things (which was of course not true at all!). He was a regular at the coffee table in the basement of the JILA tower - spending many lunches debating with Jan and Peter and others how to best make precision gravity measurements. His sharp wit and even sharper mind will be missed by all.

Click images for larger view (when available)

Your Full Name: Mariela & Stuart Reid

Briefly describe how you knew Jim: We both met and worked closely with Jim since our PhDs, where he helped us both with our many different experiments.

Your story, comment or memory: Jim would dive fully into experiments, giving them his full attention, while he worked with us to solve challenges and progress towards capturing those elusive results that have led to several publications in our field. For Stuart, as one example, Jim helped design holders (initially prototypes were carefully handmade from paper!) for shaking samples during hydroxide catalysis bonding, which verified how the underlying chemistry defined the settling time. For Mariela, he helped with sample preparation to allow thermal conductivity of silicon samples, also bonded with hydroxide catalysis bonding, to be measured. It was also very special to meet with Jocelyne and Jim in the evenings and we will treasure the memories of those times including the long talks held over evening meals. Bisous Mariela & Stuart Reid.

Your Full Name: Giles Hammond

Briefly describe how you knew Jim: I have known Jim for around 25 years. Initially this was when I was a PhD student at University of Birmingham when I worked on building torsion balances. I then spent 2 years at JILA in 1999-2001 and had many valuable scientific discussions with Jim on gravitational wave detector suspensions, more recently when Jim would visit University of Glasgow and we would discuss everything from torsion balance physics, gravimetry and gravitational waves.

Your story, comment or memory: I have spent many hours discussion physics with Jim, and my research has benefitted immensely from his unique insight and knowledge. We did not always agree in our physics discussions, but this is what made talking/sharing ideas with Jim such a great pleasure, and we always remained good friends.

Jim was extremely generous with his time, and I have seen first hand the care/passion he has for experimental physics, and how he shares this with the younger members of the community at University of Glasgow. The students he interacted with have greatly benefitted from his wisdom.

I really enjoyed discussing gravimetry with Jim, and he shared many valuable insights into how to get the best out of these delicate instruments. I will really miss his visits to the UK, and have gained so much from being his friend over the years.

Click images for larger view (when available)

Your Full Name: Konrad W. Lehnert

Briefly describe how you knew Jim: I met Jim when I first interviewed for a job in JILA while he was the NIST quantum physics division chief. Indeed got the offer and accepted the position at JILA, while Jim was our division chief.

Your story, comment or memory: I have many memories of Jim, but maybe my most important was when I was trying to stand up a lab in my first year in JILA. I was quite anxious about funding and was fretting about buying a particular piece of equipment. During my annual review I described my concern to him. He told me to buy the item and to worry about money less and research more. It was just the advice I needed to hear!

In more recent years, Jim and I had adjacent offices where I would hear him playing his french horn on weekends. I'll miss hearing him play and chatting with him about the history of JILA.

Click images for larger view (when available)

Your Full Name: Sheila Rowan

Briefly describe how you knew Jim: I have talked with Jim on his many visits to Glasgow spanning the decades from when I was young postdoc

Your story, comment or memory: Jim remained unfailingly interested equally in the precise details of experimental physics and the people who carry out the research (as well as, if I recall correctly, classical recorder music?). His deep understanding of how to make experiments work regularly helped our researchers (young and old!) do a better job. I always learned something from our discussions. I had the pleasure of visiting JILA hosted by Jim a few years ago where he arranged a series of visits for me with a wide range of staff from everywhere from the workshops to the labs to administration - he really understood how much everyone mattered in the team.

Click images for larger view (when available)

Your Full Name: Jun Ye

Briefly describe how you knew Jim: Jim was the NIST Quantum Physics Division Chief when I was hired as a JILA faculty member from the NIST side more than 20 years ago. Jim was an inspirational, caring, and strong-minded supervisor.

Your story, comment or memory: I have always enjoyed discussing scientific ideas with Jim. During the early days of the development of optical frequency combs, I came up with an idea of using a comb to perform a precise and absolute measurement for an arbitrary optical distance of a few meters to beyond thousands of kilometers. An ultrafast pulse train allows determination of absolute distance by using time-of-flight information from incoherent measurement approach (inspired by Jim's lunar ranging idea). Meanwhile, a phase-stabilized femtosecond pulse train would also allow construction of optical interferences fringes when pulses traversing different arms of an interferometer are made to overlap and interfere, given a proper adjustment of the parameters of a mode-locked laser. Essentially a “white-light” interferometry condition is created for any desired length difference between the two arms in the interferometer. Such a combined measurement capability allows an optical wavelength resolution to be achieved for absolute length measurement over a large dynamic range.

Considering Jim's outstanding contributions to optical interferometry, I discussed the idea with him and he encouraged me to write a scientific paper about it. Titled “absolute measurement of a long, arbitrary distance to less than an optical fringe” and published in Optics Letters in 2004, this paper was dedicated to Jim Faller and remains my only paper with a single author.

Click images for larger view (when available)

Your Full Name: Eric Cornell

Briefly describe how you knew Jim: Overlapped with him at JILA for two decades or so.

Your story, comment or memory: I meant to mention, in my earlier comment, about the lunar retroreflectors. More than 60 years ago Jim had the idea of installing laser retroflectors on the moon to bounce laser light back to the earth, and thus determine to very precision the distance to the moon. And, incidentally, to learn much about the internal structure and dynamics of the moon. Jim pushed this idea through NASA bureaucracy and indeed the Apollo astronauts carried with them a retroreflector array and left it in place on the moon's surface, where it has remained for 50 years. From a purely scientific point of view, Jim's lunar ranging project was the single most successful experiment to be performed by any of the Apollo missions. Amazingly, Jim's array is still in use today, and it continues to stimulate similar projects. Just a week ago (July 14,2023) the Indian space program launched a lunar landing mission. That mission includes a laser retroreflector array provided by NASA which will be an upgrade to Jim's original project. Takes quite a keen scientific vision to propose a science project that is still relevant for 60+ years!

Your Full Name: Judah Levine

Briefly describe how you knew Jim: I new Jim as a colleague for many years from the time he arrived in JILA as a Fellow until he retired. I also met Jim at Wesleyan University. He was on the faculty there, and I was applying for a junior faculty position in 1968 and 1969.

Your story, comment or memory: I worked with Jim for many years on various "precision measurement" experiments. These collaborations included work in the Poorman Mine with students from Wesleyan before Jim came to JILA as a Fellow. Jim was especially gifted in the mechanical design of experimental apparatus, and most of his work benefit greatly from his ability in this area. In particular, Jim's work on the measurement of "g" and "G" would not have been possible without very sophisticated mechanical design.

Jim was very free in providing advice to students and colleagues on sophisticated mechanical design techniques, and he worked closely with the mechanical shop personnel to teach them his methods and to suggest how the tools and machines of the shop could be improved.

In addition to our scientific and technical collaborations, I worked very closely with Jim for the two years when I was JILA chair and he was the chief of the Quantum Physics Division. Together we managed the continuity of the administrative staff after a number of retirements of senior members of the staff, and we also recruited and hired a new JILA fellow. The success of these efforts is a measure of his ability and commitment.

Click images for larger view (when available)

Your Full Name: Prof Sir James Hough

Briefly describe how you knew Jim: I met Jim properly when I was a JILA Visiting Fellow in 1983 and was totally impressed with his energy and enthusiasm for experimental physics. His wealth of stories about where he had worked and who he had worked with - particularly Bob Dicke - were fascinating, Not many physicists can claim that they were responsible for the corner cube reflectors on the moon!

Your story, comment or memory: Jim became a regular visitor to Glasgow in 2001 for several months each year and he was an inspiration to all of us. He mentored our graduate students in our Institute for Gravitational Research, helping them to think logically about what they were about to do, how to tackle experiments, how to choose, build and operate the right instrumentation for the task in hand. We all miss his visits.

Click images for larger view (when available)

Your Full Name: Nick Lockerbie

Briefly describe how you knew Jim: As a researcher myself in the field of gravity, I knew Jim initially through his worldwide reputation. Then I started to meet him in person at conferences, and eventually I was one of many having lunch with him and members of the IGR, at events hosted by the IGR in Glasgow, Scotland.

Your story, comment or memory: I remember Jim asking me at a Christmas lunch not many years since how old I thought he was. No youngster myself, I was nevertheless put to the test. I thought honesty was the best policy, but was astonished when he told me he was almost ten years older than I had thought. Smart and bright in spirit, he just appeared much younger to me than he really was!

Click images for larger view (when available)

Your Full Name: Eric Cornell

Briefly describe how you knew Jim: Jim was a Fellow here at JILA when I arrived 33 years ago, and I've known him since then. During his Division Chief days, he was my boss.

Your story, comment or memory: Jim had a keen sense for the absurdity of bureaucracy and often pointed out the needless waste of time caused

by obtuseness among the higher-ups. He prided himself on calling things as he saw them, without

fear or favor, as the saying goes. He was very generous helping me with my career when I was a

fledgling faculty member. Very early on, well before she hit the big time, Jim identified Debbie Jin as

a scientist of huge promise and he advocated vigorously for JILA to hire her. Jim had a real knack

for clever mechanical design and in the early days of diode lasers at JILA had useful suggestions

for me on how to make the lasers more immune to various vibrations shaking the floor in my lab.

Click images for larger view (when available)

Your Full Name: David Alchenberger

Briefly describe how you knew Jim: Worked with Jim on fabrication of instruments and helped him in the staff shop. He was a major contributor to the Keck Foundation grant proposal which made the JILA Keck Lab possible.

Your story, comment or memory: Mid '90's, it was uncanny how he always seem to know when we were having cake in the instrument shop office to celebrate a shop member's birthday.

Click images for larger view (when available)

Your Full Name: Hans Green

Briefly describe how you knew Jim: I am a Instrument Maker at JILA and was a colleague of Jim's for 30 years.

Your story, comment or memory: Jim was energetic, blunt and always ready with a (bad) pun. I worked closely with him on many gravity measurement instruments and his creativity, curiosity, and enthusiasm made him a pleasure to be around. Jim was a genius with precision machines and helped make me a better Instrument Maker. My life is richer for having known him. Thank you, Jim. I miss you.

Click images for larger view (when available)

Your Full Name: Jennifer Erickson

Briefly describe how you knew Jim: We worked together for about two months to clear out his setup in the spec lab.

Your story, comment or memory: Jim had a sharp mind, a sharp temper and a sharp sense of humor. On more than one occasion, I felt the need to say, "Stop being a jerk, Jim." He took it pretty well. I liked Jim, though. I enjoyed teasing him and swapping smart-alec comments. He shared his cookies with me, which always scores points. One time he came to me with a carton full of papers to shred. I told him that all of the shredding bins were full but he was free to use the decrepit shredder in my office. I brought him a chair and he sat there for hours, shredding a few pages at a time until he was up to his waist in shredded paper, like maybe he might drown. I don't think he understood why I kept laughing.

Click images for larger view (when available)

Your Full Name: Krista Beck

Briefly describe how you knew Jim: Jim and I were at JILA together for many years.

Your story, comment or memory: Jim was always so kind to the staff! When he officially retired, he invited all the staff to meet on 10th floor. There, he thanked us all for our hard work and bought us lunch! It was so long ago, but this is still such a clear memory for me. It was wonderful to feel so appreciated and spoiled! That is the person he was!

Click images for larger view (when available)