Research Highlights

Atomic & Molecular Physics | Precision Measurement | Quantum Information Science & Technology

JILA Fellow and NIST Physicist Adam Kaufman Combines Multiple Atomic Clocks into One System

Published:

PI: Adam Kaufman

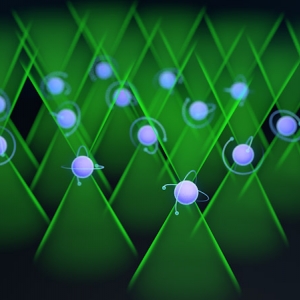

Laser Physics | Precision Measurement | Quantum Information Science & Technology

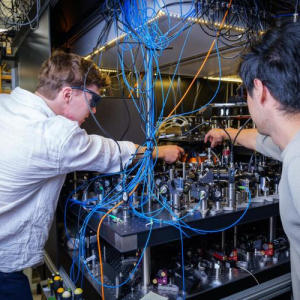

The Interference of Many Atoms, and a New Approach to Boson Sampling

Published:

PI: Adam Kaufman

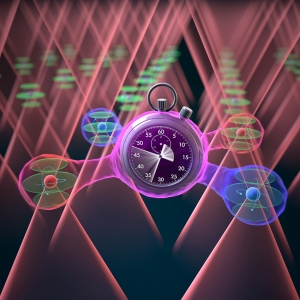

Precision Measurement | Quantum Information Science & Technology

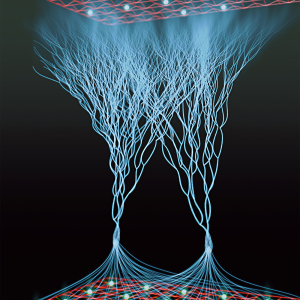

New Spin-Squeezing Techniques Let Atoms Work Together for Better Quantum Measurements

Published:

PI: Adam Kaufman | PI: Ana Maria Rey

Quantum Information Science & Technology

Seeing Quantum Weirdness: Superposition, Entanglement, and Tunneling

Published:

PI: Adam Kaufman

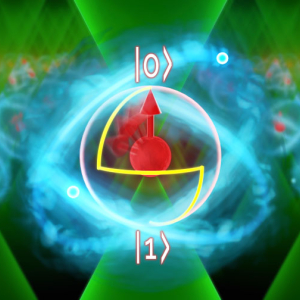

Precision Measurement | Quantum Information Science & Technology

Tweezing a New Kind of Qubit

Published:

PI: Adam Kaufman

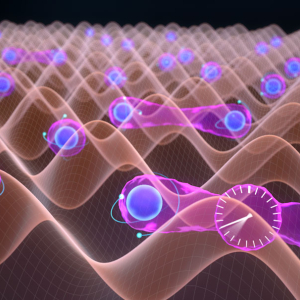

Atomic & Molecular Physics | Laser Physics | Precision Measurement

Tweezing a New Kind of Atomic Clock

Published:

PI: Adam Kaufman | PI: Jun Ye